Digital distance courses raise concerns on the future of virtual education

The Southwest bell rings. After 42 minutes of uninstructed free time, a catchy tune signals that a video call is coming from Blue Valley Northwest, and five video feeds appear on the overhead projector. Two of the five projected rooms are dark, and the announcements blare in the others. When the noise all stops, the Honors Multivariable Calculus teacher CJ Armenta assesses which schools are present and which are on an assembly schedule. One minute later, the Southwest bell rings again, signaling the end of fourth hour, but Northwest and Blue Valley High continue the lesson plan. Welcome to the Digital Bridge.

The Digital Bridge is a way for Blue Valley students to take classes that would otherwise not be offered at their respective schools. Each class meets online, and the video conference is comprised of separate video feeds from each of the schools involved. The class is taught from one of the schools and the teacher’s work is projected on to a Smartboard at every school.

When math teacher Richard Wilson told the juniors in my AP Calculus BC class that those enrolled in the Digital Bridge classes would need to work as a group in order to succeed, he was absolutely right. Strength in numbers is the only fitting motto for a class in which there is no teacher to seek help from before or after school. Originally, I disregarded what my former math teacher said, as I thought there would be nothing cooler than to have a completely digital classroom that shares a video feed with other Blue Valley students. But the distance that I thought this technology would eliminate did not shrink, it only became more obvious.

Other students, such as junior Corinne Rolfs, a veteran of the online classroom battlefield, like the system. Although Rolfs admits that the learning environment is not always ideal, she appreciates her opportunity to learn something otherwise unattainable. Without the Digital Bridge, she knows that she would not be able to continue to take Latin and learn about the rich history surrounding it. Rolfs’ unique perspective has even noticed improvement in the Digital Bridge over the years.

“As in any classroom, not everything we learn can be understood right away,” Rolfs said. “Fortunately, our teacher is very good about reviewing and practicing with us until we fully grasp each concept. It makes all the difference in the Bridge classroom. Sometimes minor sound issues occur and the screen may go blurry, but these are problems we can easily overcome. In this new year, the system is functioning better than it ever has and we have had few major mishaps.”

While valid points can be made about the opportunities that the Digital Bridge presents, I still propose that changes can be made to enhance the ease of learning at such a great physical distance.

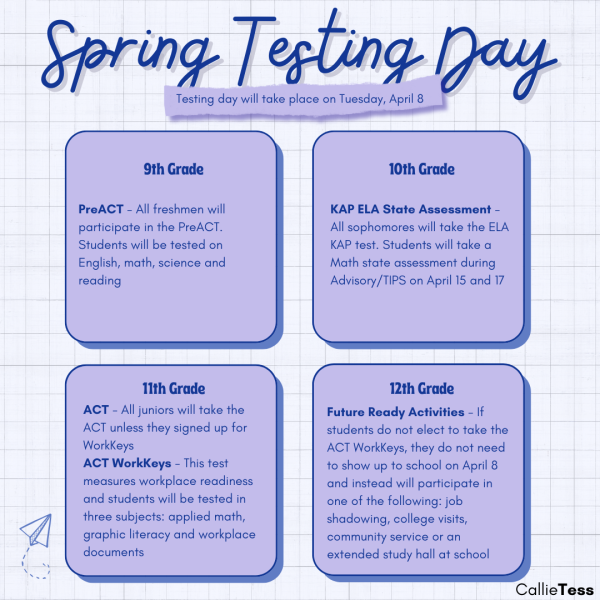

For instance, as Armenta points out that coordinating the schedules between all five schools involved is a Herculean task. Assemblies and standardized tests such as the PSAT are typically the worst schedule-manipulating events. Sometimes, Southwest students are without an instructor for an entire class period.

“I thought that all the schools would be on the same schedule,” Honors Multivariable Calculus proctor Carolyn Zeligman said. “So when our announcements get done, and there are others going on, that bothers me. It would be hard to be the teacher. How is he going to organize in an efficient manner when he’s ready to start and there are kids here who are talking, there are kids who are arriving, there are kids who are leaving? I think for something that is connected to all five schools, they’ve got to have the same schedules.”

Classroom technology is changing many school districts across the nation. Any student with a device capable of making an internet connection instantly has a deluge of information at their fingertips, but the digital infrastructure for distance video classrooms has not evolved to the mature stage that singular schools have utilized. Blue Valley Northwest German 2 teacher Elissa Schlumpf-Heymach has noticed the drawbacks of teaching a course that is heavily reli ant on person-to-person communication.

ant on person-to-person communication.

“It’s hard to make a classroom interactive sometimes, and one’s activities are limited,” Schlumpf-Heymach said. “Yes, they [digital classrooms] make it much harder, especially with pronunciation, but we try. If money was no object, it would be terrific if every student had a microphone and we could make it so that students could be paired off with each other during speaking exercises. It makes it very difficult, but one must work extra hard and put in the extra effort.”

Certainly, digital classrooms are on the right track. Forbes Magazine suggests that the confluence of multiple IP addresses and schools drastically cuts the cost of teaching the same subject as in a live classroom. They teach students the valuable lessons they will need as adults: self-advocacy, independence and adaptation, albeit in a flawed way. But before virtual classrooms become a viable method of teaching, the technological kinks and difficulties must be smoothed out.

Microphones are consistently insensitive, the video feed can become blurry and every communication always comes with a “mis” in front of it.

“I think it’s extremely distracting,” Zeligman said. “And I think if you have a classes where you have to be interactive at all, I don’t see how you can do it without be challenged by the noise from the other schools getting the attention of the teacher. I think it is hard to hear. I don’t know if teachers are aware of feedback sounds from the microphones. I sometimes think the board is hard to read, but to me the worst distraction is the noise from the other schools.”

Grant is a second-year staffer for the Standard, and likes to think of himself as the musical life of room 118. He is highly involved in music, especially...

My name is Anna Glennon and I am one of the seniors that are on staff this year. This is my second year as a photo editor for the Standard.

I don’t...